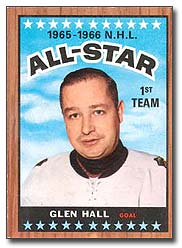

"Mr. Goalie" Glenn Hall

Hockey players, especially goaltenders, have pre-game rituals. Some are more unusual than others. But no one had a stranger ritual than former NHL goaltending great Glenn Hall who, because of nerves, would literally become physically ill while waiting the start of a game.

Hockey players, especially goaltenders, have pre-game rituals. Some are more unusual than others. But no one had a stranger ritual than former NHL goaltending great Glenn Hall who, because of nerves, would literally become physically ill while waiting the start of a game.

More often than not, before the first face-off, during the rest periods or after the game was concluded, Glenn quietly and unobtrusively would throw up .

"I always felt I played better if I was physically sick before the game. If I wasn't sick, I felt I hadn't done everything I could to try to win," Hall once said.

It obviously worked for Hall, as the man nicknamed "Mr. Goalie" has to be considered a prime candidate as the greatest goalie ever played.

Glenn Hall is also renowned as the grandfather of the butterfly goalie. He was the first goalie to practice and perfect the now common butterfly stance, as he'd fall on knees, spread his legs to take away the bottom corners and five-hole and let his rapier-like arm reflexes take care of the top corners. Glenn would meet the shot with his feet wide but his knees close together to form an inverted Y. Instead of throwing his whole body to the ice in crises, he would go down momentarily to his knees, then bounce back to his feet, able to go in any direction. Practically every goalie in hockey today relies on the strategies he perfected.

During his 18-year NHL career, which began in 1952 and ended in 1971, Glenn posted a 407-327-163 record, 2.51 goals-against-average and recorded 84 shutouts. He was a First Team All-Star seven times, won three Vezina Trophies, was voted the league's top rookie in 1955-56 and was awarded the Conn Smythe trophy in a losing cause in 1968. Despite his lengthy career, Glenn won his only Stanley Cup with the Blackhawks in 1961—the last time Chicago captured the title.

Hall actually started his career buried in the Detroit Red Wings system in the early 1950s. With the great Terry Sawchuk established as the number one goalie, it seemed as though Hall would have to wait forever for his turn to get a chance at full-time play in the league. But Hall kept the pressure on Sawchuk, eventually leading to the surprising Sawchuk trade to the Boston Bruins in 1955. Hall took to the Red Wings crease, and turned in a memorable rookie season, coming within one shutout of Harry Lumley's modern record of 13 set two seasons previously. He allowed only 2.11 goals against as he played in each and every game and won the Calder Trophy as the NHL's top rookie.

Hall played one one more season with Detroit, before yet another shocking trade involving a Red Wings goalie. This time Hall was packaged up in the infamous Ted Lindsay trade to the Chicago Blackhawks.

It was in Chicago that Hall is best remembered.  Hall was a huge part of the Blackhawks turnaround, backstopping them to the Stanley Cup championship in 1961. The Hawks became the toast of Chicago for much of the 1960s, selling out every ticket for 14 seasons. With the likes Pierre Pilote, Stan Mikita and Bobby Hull, the Hawks were hot. But it was Hall who was synonymous with the Hawks, playing seemingly every game. In fact, despite his taxing pre-game ritual, Glenn holds the NHL record for most consecutive complete games, 502, by a goaltender. That's 502 straight contests without missing a minute of play. Not one single minute over the span of 8 seasons. That is one record that is certain never to be broken. Even more amazing is he accomplished this feat while playing without a mask.

Hall was a huge part of the Blackhawks turnaround, backstopping them to the Stanley Cup championship in 1961. The Hawks became the toast of Chicago for much of the 1960s, selling out every ticket for 14 seasons. With the likes Pierre Pilote, Stan Mikita and Bobby Hull, the Hawks were hot. But it was Hall who was synonymous with the Hawks, playing seemingly every game. In fact, despite his taxing pre-game ritual, Glenn holds the NHL record for most consecutive complete games, 502, by a goaltender. That's 502 straight contests without missing a minute of play. Not one single minute over the span of 8 seasons. That is one record that is certain never to be broken. Even more amazing is he accomplished this feat while playing without a mask.

At the age of 36, he was left unprotected in the 1967 Expansion Draft and was chosen by the newly minted St. Louis Blues. Due in large part to Hall's improbable heroics, the Blues marched all the way to the Stanley Cup final in their first year in the league. Though they would eventually lose to the Montreal Canadiens in four games, Hall was awarded the Conn Smythe Trophy as the league's top playoff performer. In 1968-69, Jacques Plante joined the team and the two veterans shared the goaltending duties, and split the Vezina Trophy. The duo returned the Blues to the Stanley Cup finals in both 1969 and 1970, only to lose again.

Hall retired in 1971, returning to Alberta to tend to his farm, while working with the Blues and later Calgary Flames as a goaltending coach and consultant.